[O]n the lonely side of Mount T'ai

[Confucius] heard the mourning wail of a woman. Asked why she

wept, she replied, "My husband's father was killed here by a

tiger, my husband also, and now my son has met the same

fate."

"Then why do you dwell in such a dreadful place?"

Confucius asked.

"Because here there is no oppressive ruler," the woman

replied.

- from The World's Religions by Huston Smith

It is said that what is called "the spirit of an age" is something to which one cannot return. That this spirit gradually dissipates is due to the world's coming to an end. For this reason, although one would like to change today's world back to the spirit of one hundred years or more ago, it cannot be done. Thus it is important to make the best out of every generation. - Hagakure

How does a society find the right balance between anarchy and tyranny? How much government is too much; how little is too little? This is the question that preoccupied the mind of a great philosopher and humanitarian, K'ung the Master, known to the West as Confucius.

K'ung lived long ago in China, in an era known as "the Period of the Warring States," in which social cohesion had deteriorated to a critical point and lawlessness prevailed. He wanted to correct that deterioration via a social philosophy which found a proper balance between the extremes of depending on coercion and trusting in love. He came up with the concept of "deliberate tradition," which meant taking the guidance of ancient wisdom, and reformulating it in light of contemporary developments. He sought to bring heaven to earth by the systematic application of principles of living to the particular society of a certain time and place.

K'ung figured that the issue of how strong government should be would settle itself easily enough if the government was just and proper. Insuring that authority remained legitimate was the goal of deliberate tradition. Doing so required adhering to key principles: respect for humanity, the cultivation of the individual, rules for proper living, the just use of power, and the improvement of human nature through high culture. A society which obeyed these principles would naturally be harmonious.

So, did his plan work? Well, Confucius has been revered in China for over 2000 years - his wisdom shines on in this present age. But his homeland has been through many dynasties, good and bad, since he died in 479 B.C., and is now ruled by a pseudo-Marxist regime notorious for its oppressions. Clearly, his principles have not been respected with the utmost diligence. But one could hardly expect the harmony Master K'ung sought to be maintained indefinitely - to do so would be to expect time to stand still!

History never obliges any philosopher by reaching some definable moment and then staying there - every era must eventually end. When governments are formed by thoughtful and well-thought-of men, their days of glory are numbered. However inspired the founders of a state, however authoritative its first rulers, eventually its prestige is exhausted and, as entropy takes its toll, civic disorder spreads throughout the country.

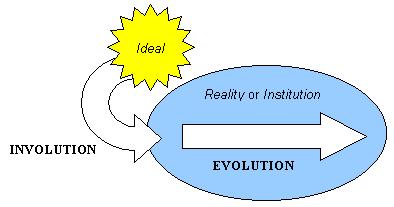

The ancient historian Polybius identified a natural progression of government from monarchy to aristocracy to democracy to anarchy, with an inevitable return to monarchy when someone of strong character and resolve arose to restore order and establish a new dynasty. If the founding act at this cycle's inception is thought of as one of fundamental creativity, then the playing out of a regime's history can be seen as its evolution following the involution of its ideal in the initial decrees and covenants which instituted it.

Since the process of evolution is one of limited creative potential, thanks to the world's coming to an end, and the spirit which inspired the founding act gradually dissipates, eventually the newly instituted government becomes a decrepit dinosaur and its subjects lose all faith in it. At that point, a renewal of the spirit of proper rule - however defined by the people alive at the time - is required. The corrupted and ruined regime is swept away in a political revolution, and a new one rises in its place.

When does a government become illegitimate and its destruction a just fate? Who decides that? These important questions underlie the history of a paradoxical and unprecedented nation, the United States of America. Founded on an abstract ideal of what is right, it owes its existence to the practical application of might in three great wars. Its institutions are among the wealthiest, most prominent and most maligned today. It is the envy of nations, and the first to be blamed for most of the world's problems.

America's uniqueness and inherent contradictions have been explained in a cyclical context by Samuel Huntington. in his work "American Ideals versus American Institutions". In it, Huntington describes how, when a generation arises which is dissatisfied with how America's institutions are not living up to its ideals, it propels a new movement for reform which eventually catalyzes a revolution.

Those dudes in wigs, the Founding Fathers, weren't especially adept at figuring out what makes a governement illegitimate and recognizing the traits in the British crown. They were just rebellious at exactly the right time to start something new. If Huntington is correct, this time comes around once every few generations, when the nation is reinvented, sometimes in a catastrophic conflict. In this manner, America lurches towards its ultimate destiny, whatever that is.

A simple, linear approach to America's history considers it an independent nation which began in 1776 and is now a little over two and a quarter centuries old. A cycle-oriented understanding of the history of the United States insists that there have been three regimes.

The first American regime, the Republic, emerged from victory against Britain in one war (1789) and was established for certain by victory in another (1812). It explored and settled a virgin continent, pushing its frontiers to the far ocean, but as it expanded it was strained by the contradictions between its principles and its socioeconomic realities. Its commitment to freedom stood in glaring contrast to its population of enslaved Africans, and the conflicting needs of the agrarian economy of its southern States and the commercial and manufacturing economy of its northern States challenged confederation. The strain became too great to bear and the Republic split asunder, reuniting only after a fearsome war which left more men dead than any war the nation had fought before or has fought since. The dividing line marked by the armies of 1861 is visible in the culture of America to this day.

Lincoln's victory of 1865 birthed the second American regime, a rejoined Union of States and Territories, new, old and reconstructed. Unabashedly capitalist and industrialist, led in its early years by the bloody-shirted veterans of the recent war, this regime brushed off the election crisis of 1876 (when sixteen years earlier an election crisis had precipitated secession), as its citizens set about the busy work of putting its vast landholdings to productive use. Even as it thrust the American people into the forefront of industrial revolution, it defied their consciences with its powerful trusts, ruthless robber barons, and capricious currencies. After the tides of economic booms and busts broke against the hard shoreline of a global depression, its spirit was revitalized by the threat of vicious foreign powers, and its energies marshalled for the greatest struggle humanity has ever known.

Over the ruined battlefields of the total victories of 1945 towered the third American regime, the Superpower champion of freedom, its mission complicated immediately by the antagonism of a dangerous and devious Communist enemy. Its leaders embarked on a new, "cold" war without subtlety, investing in a nuclear arsenal to counter the conventional forces of the Soviet Union, and engaging in far-flung conflicts which were eventually judged futile at best and monstrous at worst. Its militaristic policies ultimately delegitimized in the public's eye, it perservered nonetheless thanks to the superior economic power of the nation. Now it is threatened by insidious new foes and an unsympathetic world. Her institutions completely discredited, her leadership cast perpetually in doubt, America still awaits the clarion call that will lead her into the next great age - or perhaps to her dissolution.

We can not return to a previous age. Lovers of liberty are right to invoke the wisdom of the Founding Fathers, but wrong to think we can possibly return to the days of their idyllic Republic, or that Washington's ghost will arise to disentangle us from global alliances. Defenders of the free market are right to laud the achievements of the great capitalists, to whom the nation owes its spectacular wealth, but wrong to believe we can completely dismantle the government infrastructure that was erected in the wake of the disaster of 1929, or that laissez faire economics will ever erase from itself the stigma of exploitation. History moves in one direction!

It is inevitable that man's institutions should fall short of his ideals, and that his ideals can only be realized by focusing energy on the construction of imperfect institutions. That humankind's dreams can never fully materialize is just a sad consequence of her nature, poised halfway between heaven and earth...

What a piece of work is a man! how noble in reason! how infinite in faculty! in form and moving how express and admirable! in action how like an angel! in apprehension how like a god! the beauty of the world! the paragon of animals! - Hamlet Act 2, Scene 2

Ideas about cycles of history inspired by William Strauss and Neil Howe, The Fourth Turning, 1997, Broadway Books. The descriptions of the three American regimes imitate their cogent synopses of American saecula. Learn more at www.fourthturning.com.

Confucius information and story is from Huston Smith, The World's Religions, 1991 HarperCollins.

The quote from Hagakure is taken from the movie Ghost Dog.

This page copyright Steve Barrera 2001-2024